Quick facts

Common name - Honey fungus

Scientific name - Armillaria (several species)

Plants affected - Many woody and herbaceous perennials

Main symptoms - Decaying roots, white fungus between bark and wood, rhizomorphs, sudden death of plant

Caused by - Fungus

Timing - Mycelium and rhizomorphs present all year, mushrooms only late-summer to autumn

What is honey fungus?

Honey fungus is the common name of several species of fungi within the genus Armillaria. Honey fungus spreads underground, attacking and killing the roots of plants and then decaying the dead wood. It is the most destructive fungal disease in UK gardens.

Honey fungus can attack many woody and herbaceous . No plants are completely immune, but there are some that are only rarely recorded as being affected (see the 'Control' section below).

Aesculus, Betula (birch), Buddleja, Ceanothus, Cedrus, Cercidiphyllum, Cotoneaster, × Cuprocyparis leylandii (leyland cypress), Forsythia, Juglans, Laburnum, Ligustrum (privet), Liquidambar,Photinia, Quercus, Rhododendron(azalea), Salix (willow), Sorbus, Syringa (lilac), Thuja, Viburnum and Weigela are all particularly susceptible to honey fungus.

Symptoms

Some of the symptoms you may see:

Above ground

- Upper parts of the plant die. Sometimes suddenly during periods of hot dry weather, indicating failure of the root system; sometimes more gradually with branches dying back over several years

- Smaller, paler-than-average leaves

- Failure to flower or unusually heavy flowering followed by an unusually heavy crop of fruit (usually just before death of the plant)

- Premature autumn colour

- Cracking and of the at the base of the stem

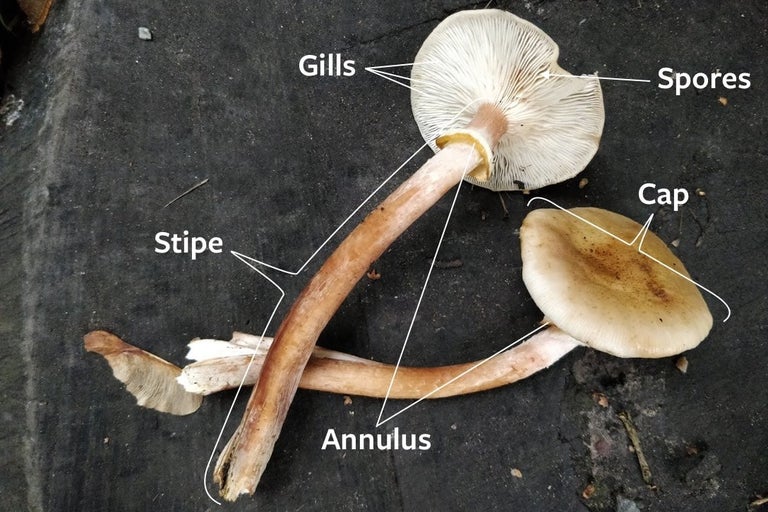

- If suitable conditions permit, mushrooms are produced in autumn from infected plant material

Below ground

- Dead and decaying roots, with sheets of white fungus material (mycelium) between bark and wood, smelling strongly of mushrooms. This can often be detected at the collar region at ground level, and more rarely spreads up the trunk under the bark for about 1m (3¼ft). This is the most characteristic symptom to confirm diagnosis

- Rhizomorphs (see images 2, 3 and 4 above) are often difficult to detect, especially for the most pathogenic species, and they are particularly difficult to find in the soil

Control

There are no chemicals available for control of honey fungus. If honey fungus is confirmed, the only effective remedy is to excavate and destroy, by burning or landfill, all of the infected root and stump material. This will destroy the food base on which the rhizomorphs feed and they are unable to grow in the soil when detached from infected material.

Non-chemical control

To prevent honey fungus spreading to unaffected areas, a physical barrier such as a 45cm (18in) deep vertical strip of butyl rubber (pond lining) or heavy duty plastic sheet buried in the soil will block the rhizomorphs. It should protrude 2-3cm (about 1in) above soil level. Regular deep cultivation will also break up rhizomorphs and limit spread.

Avoid the most susceptible plants and instead use plants that are rarely recorded as being affected by honey fungus. Some less affected plants include: Arundinaria (and other bamboos), Buxus sempervirens, Callicarpa, Catalpa, Chaenomeles, Chimonanthus, Cordyline, Erica, Garrya, Ginkgo, Hypericum, Jasminum, Pittosporum, Rhamnus, Sarcococca, Tamarix, and Vaccinium.

See this link for a more complete list of susceptible and less affected woody plants.

There are very few records of honey fungus affecting any member of the grass family. This suggests that ornamental grasses could be a good option for growing in areas of a garden where honey fungus is present, although to our knowledge the susceptibility of different grass species and cultivars has yet to be evaluated experimentally.

Chemical control

There are no chemical controls available.

SURVEY: Do you grow privet in your garden?

Our most susceptible known host is Ligustrum (privet), but recent studies at the 911���� have shown that some species of privet are more resistant than others.

We would love to hear from you about what species of privet you have in your garden and how you grow it. We also want to hear if you’ve ever seen honey fungus root rot or mushrooms in your garden. We aim to use this information to improve our honey fungus resistance index. This will help us recommend species that are more likely to thrive when replanting after a honey fungus outbreak.

Do you grow privet? Tell us here

You can help our research by filling in our short survey, having identified which of three common types of privet you have using the quick guide below.

As privet is our most important honey fungus host, this survey will be running long-term. The first six weeks of data will contribute to a summer studentship research project and results will be shared in an August Hilltop Live by the student, Mary Coates (University of York). Thank you for taking part in this project!

How to identify your privet

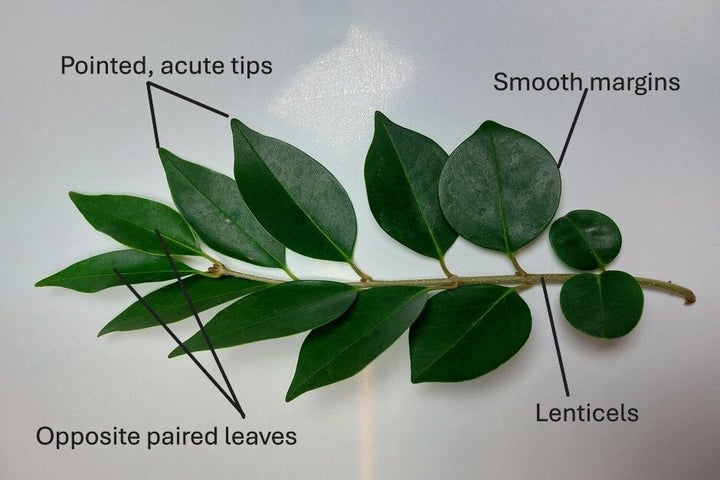

Our survey aims to map the distribution of different species of privet, but you might not know what species you have growing in your garden. To help with this, please use the images below, which provide a brief description of the identifiable features of the three species featured in our survey.

Privet plants have leaves that are arranged in opposite pairs along the stem, with smooth (untoothed) margins. The flowers are white or off-white, growing at the end of the stems. A distinct feature of privet flowers is that they have four petals and two pollen-bearing stamens at the centre (see above). The fruit are small, round and purplish-black. All privet plants have white lenticels (spots) visible on the stems, although they are less visible on new shoots.

L. vulgare (wild privet) is a semi-evergreen plant, meaning that some leaves are lost in winter – this makes it more than the other species. It also has narrower leaves, which often measure between 3-6cm in length and 1-3cm in width. A distinct feature of L. vulgare is that the stems are are covered in dense, minute hairs, which are absent in both L. ovalifolium and L. lucidum. The hairs can be seen using a hand lens (see image below).

L. ovalifolium (oval-leafed privet) is a semi-evergreen plant with hairless stems and fewer lenticels (white dots on stem) than other species. Leaves are oval-shaped with quite blunt tips that are less pointed than L. lucidum, which it is likely to be confused with. Leaves range from 2.5-8cm in length and 1.5-3cm in width.

L. lucidum is an evergreen plant that does not lose its leaves in winter. It has the largest and thickest leaves of all species in our survey, ranging from 6-16cm in length and 3.5cm in width. Leaves typically have a short, sharp point at the tip, making them look more pointed than L. ovalifolium. The stems are hairless, but typically have more lenticels (white dots on stems) than the other species.

Biology

There are seven species of Armillaria in the UK. The most common species in gardens are A. mellea and A. gallica. There is a rarer occurrence of A. ostoyae. The remaining species A. cepistipes, A. tabescens, A. borealis and A. ectypa have not been found in gardens according to a survey done by 911���� scientists. A. mellea and A. ostoyae are the most damaging species. A. gallica is considered to be less damaging although more research is needed to find out how destructive these species are.

The fungus spreads underground by direct contact between the roots of infected and healthy plants and also by means of black, root-like structures called rhizomorphs (often known to gardeners as ‘bootlaces’), which can spread from infected roots through soil, usually in the top 15cm (6in) but as deep as at least 45cm (18in), at up to 1m (3¼ft) per year. It is this ability to spread long distances through soil that makes honey fungus such a destructive pathogen, often attacking plants up to 30m (100ft) away from the source of infection.

Clumps of honey-coloured mushrooms (see images 5 and 6 above) sometimes appear briefly on infected stumps in autumn. However, the absence of mushroooms is no indication that the fungus is not active in the soil and many plants may be killed before mushrooms appear.

Early indications from ongoing 911���� research suggest that spores from the mushrooms of Armillaria mellea are more important in spreading the fungus than previously thought. The variability found between samples of the fungus taken from different areas of the garden at 911���� Wisley indicates that many of the initial infections arose from spores (although once established in a particular area the fungus will still then spread between adjacent plants via rhizomorphs or root-to-root contact).

A. gallica produces large and easily visible rhizomorphs quite often found in heaps. As a precaution, do not use infested compost around woody plants.

Read more by visiting our page on 911���� research on honey fungus and other diseases.